MVC 2018: Advances in Feline Heart Disease Diagnosis

Combining radiology, echocardiography, and cardiac stress marker results can bring clarity to ambiguous cases.

About half of cats with murmurs have diagnosable cardiac disease.

Cats are more adept than dogs at hiding clinical signs of heart disease, according to Rebecca Stepien, DVM, DACVIM, clinical professor of cardiology at the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine. That’s why it is important to use multiple available diagnostic tools to detect and stage cardiac disease in cats. At the 2018 Midwest Veterinary Conference in Columbus, Ohio, Dr. Stepien presented the latest tools for diagnosis of cardiac abnormalities in cats. She began by emphasizing the importance of differentiating heart disease and heart failure in the feline patient.

Differentiating Heart Disease and Heart Failure

Cardiac disease, she said, is typically monitored rather than clinically treated in cats, whereas cardiac failure is almost always treated. Heart disease is defined as a physical or functional abnormality of 1 or more components of the cardiovascular system; heart failure occurs when cardiac output provides inadequate blood pressure for organ perfusion despite normal hydration status. Cardiac failure may manifest clinically as hypotension due to low cardiac output or as congestion, edema, or other fluid accumulation due to sodium and/or water retention.

RELATED:

- ACVC 2016: Hyperthyroidism in Cats - What You Need to Know

- New Heart Disease Drug May Help Both Cats and People

Detecting asymptomatic heart disease in cats is not a straightforward process. Dr. Stepien estimated that approximately one-quarter to one-third of overtly healthy cats have heart murmurs. About half of cats with murmurs have diagnosable cardiac disease, while in the other half the murmurs are innocent. Dr. Stepien emphasized, “No murmur likely means no disease.” She added that the most common life stage for development of myocardial disease begins at about 6 to 8 years of age and decreases after 12 to 14 years.

Gallop Rhythm and Cardiac Arrhythmia

To determine whether a heart murmur is causing disease, Dr. Stepien advised examining for additional abnormal findings, especially a gallop heart sound or cardiac arrhythmia. Gallop heart sounds occur when rapid ventricular filling suddenly stops because of abnormal stiffness of the ventricular wall, thus generating a third heart sound. The condition, which may be temporary or permanent, can be caused by a variety of pathologies, including hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, ventricular fibrosis (eg, restrictive cardiomyopathy), and neoplasia. In particular, Dr. Stepien noted, feline lymphoma can infiltrate and stiffen the heart wall. Increased ventricular dilation leading to gallop heart sounds can also occur in patients with renal disease after receiving fluid therapy because of overhydration and increased blood volume. The combination of a cardiac murmur and an arrhythmia also increases the likelihood of true cardiac disease, she said.

Heart Murmur in a Healthy Cat: Should I Still Worry?

A heart murmur may warrant additional investigation even in patients with no outward clinical signs, Dr. Stepien noted. Further diagnostics should be performed before any cat with a murmur undergoes anesthesia or receives fluid therapy. Also, certain systemic diseases, such as occult hypertension, anemia, and hyperthyroidism, can exacerbate a murmur and should be ruled out. Finally, some clients may encourage further diagnostics for peace of mind.

Diagnostic Imaging for Cardiac Abnormalities

Dr. Stepien noted that radiology is more useful than echocardiography for assessing congestive heart failure, but echocardiography is needed to evaluate cardiac anatomy. Many cats with cardiac disease lack significant atrial and/or ventricular enlargement on radiographs but will show enlargement when imaged by echocardiography. Obese cats frequently deposit fat in the pericardium, thus enlarging the cardiac silhouette on radiography even in the absence of cardiac disease. In such cases, Dr. Stepien advised examining the pulmonary vessels as an additional indicator of cardiac disease. She also noted that if the heart touches the diaphragm, it is likely enlarged.

Another limitation of radiography is the large overlap in vertebral heart scores between normal and abnormal cats. According to 1 study, a vertebral heart score of 8 or higher is only 78% sensitive for detecting left heart disease with no or mild left atrial enlargement1; however, sensitivity increases to 91% if left atrial enlargement is mild to moderate. Study results showed that vertebral heart score was 82% specific for detecting left heart disease, regardless of left atrial size. Therefore, vertebral heart score may be an unreliable predictor of cardiac disease. Dr. Stepien emphasized the use of echocardiography, particularly for detecting preclinical heart disease in cats. An echocardiogram provides direct information on heart structure, such as wall thickness and chamber size, as well as function. In particular, Doppler echocardiography is valuable for assessing systolic and diastolic function. An echocardiogram can also identify pleural effusion, diaphragmatic hernia, and mass lesions and can differentiate between benign and disease-related causes of heart murmur and gallop heart sounds. In short, echocardiography is an incredibly useful tool to help rule in or out heart disease.

Echocardiography holds particular value for screening at-risk cat breeds, including the sphynx and Maine coon, for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy before breeding. As noted earlier, diagnostics such as echocardiography should be performed before administering anesthesia or fluid therapy in patients with heart murmurs. Echocardiography is also the most effective tool for detecting intracardiac thrombi. Dr. Stepien noted that thoracic ultrasound is much less stressful than radiographs to perform on an unstable patient, and even a brief or limited scan can still provide valuable information, such as the presence or absence of pleural effusion. She allows particularly fragile patients to remain sternal and receive supplemental oxygen rather than placing them in lateral recumbency. Dr. Stepien emphasized looking at the left atrium, which will likely be enlarged in a cat with signs of congestive heart failure, such as pleural effusion and pulmonary edema. A left atrium measuring more than 1.5 times the diameter of the aorta likely indicates heart disease.

Thoracic ultrasound can also detect the presence of lung infiltrates related to heart disease, as in cases of pulmonary edema. The dorsal lung field offers an ideal location to view lung tissue by orienting the ultrasound probe between the ribs. Although the appearance of white horizontal lines, or A lines, is normal on thoracic sonography, fluid in the lungs will cause white vertical lines or “rockets” that descend vertically from the probe location.

Although echocardiography remains the gold standard for diagnosing heart disease in cats, Dr. Stepien acknowledged that many veterinarians lack access to this tool. “That doesn’t keep you from being a good practitioner,” she assured the audience. Recent advancements in cardiology include measurement of cardiac stress markers, she said.

BNP Measurement

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is a hormone that regulates blood pressure and fluid balance through renal sodium and water loss as well as vasodilation. BNP is synthesized and stored in the cardiac myocytes as the promolecule proBNP. Secretion of proBNP by the myocytes is continuous and increases with excessive stretching, pressure, or expansion of the cells. Because many forms of heart disease, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, cause excessive stretching of the heart muscle, BNP is an appropriate marker for assessing for the presence of heart disease. In general, the amount of circulating BNP correlates with severity of cardiac stress.

ELISA and SNAP Tests

In veterinary medicine, quantitative and semiquantitative tests are available to estimate plasma N-terminal (NT)-proBNP concentrations. The measured form of BNP, NT-proBNP, is 1 cleaved end of the secreted proBNP molecule. NT-proBNP is stable and has a long half-life, making it a good indicator of circulating BNP concentrations.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) NT-proBNP test is available from Idexx as the feline CardioPet proBNP test, which provides a quantitative result, as the amount of visible marker is proportional to the amount of circulating BNP. The SNAP feline semiquantitative test provides a positive or negative result for NT-proBNP, with a cutoff value of about 150 pmol/L. A “very dark” positive dot indicates a relatively high value, suggesting more severe cardiac stress.

Interpreting High BNP Concentrations

Heart disease and heart failure both raise NT-proBNP levels2-4; however, increased NT-proBNP may occur in patients with “normal” echocardiogram findings. In such cases, it is important to rule out other causes of increased NT-proBNP. Several diseases, including systemic hypertension5 and hyperthyroidism,6 may increase NT-proBNP by affecting blood volume or cardiac work—related stress. Concentrations may also rise in cats with true renal insufficiency or prerenal azotemia due to dehydration, as NT-proBNP excretion occurs in the kidneys. Dr. Stepien noted that renal disease appears to have a lesser effect on NT-proBNP concentration in cats than in dogs and humans.

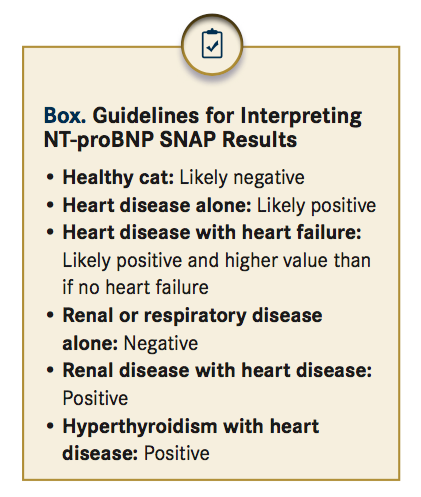

As a general rule, the greater the NT-proBNP concentration, the more severe the abnormality is. Primary cardiomyopathy causes higher NT-proBNP concentrations compared with secondary cardiomyopathy due to hyperthyroidism or hypertension. Heart disease cases also have higher NT-proBNP values than cases of impaired NT-proBNP excretion due to renal disease. Dr. Stepien added that congestive heart failure usually corresponds to higher NT-proBNP values than does heart disease alone. She provided general guidelines for interpreting NT-proBNP SNAP results (BOX).

Although the exact cutoff values are not clear, 1 study determined that a quantitative NT-proBNP test result of 99 pmol/L or higher effectively detected subclinical cardiomyopathy (sensitivity 71%, specificity 100%).4 Results from another study showed that dyspneic cats with a plasma NT-proBNP value above 265 pmol/L were likely to have heart failure (sensitivity 90%, specificity 88%).3 Cats with congestive heart failure had a median NT-proBNP value of 754 pmol/L, and 90% of values exceeded 300 pmol/L.3 A higher NT-proBNP value, Dr. Stepien stated, should increase confidence in a congestive heart failure diagnosis.

Quantitative NT-proBNP measurement using ELISA can also help clarify ambiguous situations, such as differentiating innocent murmurs from associated disease or correlating respiratory signs with heart failure.

NT-proBNP assessment, however, does have limita- tions. The test cannot specify the type of heart disease present, nor will it provide an indication for therapy. Also, research has not yet established whether NT-proBNP measurement can reliably detect preclinical genetic disease. The value of NT-proBNP measurement, Dr. Stepien stressed, lies in aiding interpretation of other clinical findings.

Which Test Should I Choose?

Clinical applications differ for the semiquantita- tive SNAP and quantitative ELISA tests, Dr. Stepien stated. The SNAP test is best used when the extent of cardiac stress needs to be determined immediately, as the quantitative test costs more and has a 12- to 24-hour turnaround time. The SNAP test is also particularly valuable for confirming suspect-normal cases, particularly before administering anesthesia or fluid therapy. Examples include a relatively low-risk, young cat with a murmur or a dyspneic cat with a history of respiratory disease but no history of cardiac disease.

Dr. Stepien reminded the audience that the cutoff value of 150 pmol/L NT-proBNP for the SNAP test is similar to the approximately 100 pmol/L cutoff for asymptomatic heart disease.4 Therefore, a positive SNAP test likely indicates the presence of heart disease, whether subclinical or clinical.

Dr. Stepien recommended the quantitative ELISA test for suspect heart disease cases for which an echocardiogram cannot be performed, as the quantitative test still provides an indication of disease severity. The quantitative test can also help track heart disease cases over time as well as provide further clarity after a positive SNAP test result.

My Patient Has Elevated BNP Levels. Should I Treat for Cardiac Disease?

Dr. Stepien reminded the audience that a positive SNAP or ELISA NT-proBNP test result should always be interpreted in combination and other diagnostic findings. "This way," she said, "one can look for suggestive evidence of heart failure, such as auscultatory or radiographic abnormalities, arrhythmia, and dyspnea." Treatment should be initiated if clinical signs indicate cardiac failure.

Caveats of Measuring NT-proBNP

No diagnostic test is perfect, and the NT-proBNP test has limitations. The test is more sensitive than echocardiography; therefore, NT-proBNP levels may rise before abnormalities are visible on an echocardiogram. Likewise, marginal increases in NT-proBNP may occur because of other diseases5,6 or may hover close to the cutoff point for abnormality.7 Finally, a patient’s NT-proBNP values can vary as much as 13% day to day and 21% week to week.8

In summary, the NT-proBNP test is particularly helpful for cases in which ruling out heart disease helps avoid more costly evaluation or for those in which physical examination and diagnostic tests have provided inconclusive evidence of heart disease.

Closing Remarks

Evaluation of feline cardiovascular disease should include a combination of available diagnostic tools, including physical examination, thoracic radiography, electrocardiography (in cases of arrhythmia), echocardiography, and NT-proBNP measurement. Diseases with secondary cardiac effects, such as hyperthyroidism and renal disease, should also be considered in cats with cardiac abnormalities.

Dr. Stilwell received her DVM from Auburn University, followed by a MS in fisheries and aquatic sciences and a PhD in veterinary medical sciences from the University of Florida. She provides freelance medical writing and aquatic veterinary consulting services through her business, Seastar Communications and Consulting.

References:

- Guglielmini C, Baron Toaldo M, Poser H, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vertebral heart score and other radiographic indices in the detection of cardiac enlargement in cats with different cardiac disorders. J Feline Med Surg. 2014;16(10):812-825. doi: 10.1177/1098612X14522048.

- Connolly DJ, Magalhaes R, Fuentes VL, et al. Assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of circulating natriuretic peptide concentrations to distinguish between cats with cardiac and non-cardiac causes of respiratory distress. J Vet Cardiol. 2009;11(suppl 1):S41-S50. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2009.03.001.

- Fox PR, Oyama MA, Reynolds C, et al. Utility of plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) to distinguish between congestive heart failure and non-cardiac causes of acute dyspnea in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;11(suppl 1):S51-S61. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2008.12.001.

- Fox PR, Rush JE, Reynolds CA, et al. Multicenter evaluation of plasma N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP) as a biochemical screening test for asymptomatic (occult) cardiomyopathy in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25(5):1010-1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00776.x.

- Lalor SM, Connolly DJ, Elliott J, Syme HM. Plasma concentrations of natriuretic peptides in normal cats and normotensive and hypertensive cats with chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;11(suppl 1):S71-S79. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2009.01.004.

- Sangster JK, Panciera DL, Abbott JA, Zimmerman KC, Lantis AC. Cardiac biomarkers in hyperthyroid cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28(2):465-472. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12259.

- Harris AN, Beatty SS, Estrada AH, et al. Investigation of an N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide point-of-care ELISA in clinically normal cats and cats with cardiac disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31(4):994-999. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14776.

- Harris AN, Estrada AH, Gallagher AE, et al. Biologic variability of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in adult healthy cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2017;19(2):216-223. doi: 10.1177/1098612X15623825.