A Practical Guide to Feline Retrovirus Testing

Knowing when and how to test for feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus will enable optimal care for feline patients.

Testing and segregation form the bedrock of feline retrovirus control in veterinary clinics, shelters, and homes, according to Susan Little, DVM, DABVP (Feline Practice), who co-owns 2 feline practices in Canada. “These retroviruses are not going anywhere,” she emphasized, “so we need to be continually vigilant.”

In a recent webinar hosted by Idexx, Dr. Little discussed recommendations for retrovirus testing in cats in various situations.

Testing For Feline Immunodeficiency Virus

Currently available feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) tests detect either anti­bodies against the virus or the presence of viral nucleic acid, Dr. Little said. Point-of-care (POC) test kits used in clinics and shelters detect soluble antibodies that target various FIV antigens.

Referral laboratories also conduct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as a screening test, as well as antibody-based Western blotting (targeting more antigens than the in-clinic test targets) and poly­merase chain reaction (PCR) testing as follow-up tests to detect viral proviral DNA, viral DNA, or both.

Point-of-Care Test Kits for FIV

Various POC tests can now be used in the clinic to detect FIV, and all perform well. One recent inde­pendent study compared performance among 4 POC tests and found no significant differences for FIV diagnosis—all showed reasonably good sensitivity and specificity for FIV.1 These tests use ELISA and rapid immunomigration technology.

When using a POC test to screen for FIV in an adult cat, if the result is positive, Dr. Little advised retesting immediately using a different kit, especially if the cat has received an FIV vaccination. If possible, choose a kit that is more likely to discriminate between FIV vaccine antibody and natural infection, she recom­mended. Alternatively, veterinarians could just use a validated PCR test, she said.2

How FIV Vaccination Affects FIV Testing

Even though an FIV vaccine is no longer available in the United States or Canada, differentiating between antibodies resulting from natural infection and those arising from vaccination remains a problem, according to Dr. Little. “Some cats with FIV-vaccine—induced anti­bodies will continue to test positive for FIV antibodies for years after their last vaccination,” she said, under­scoring the need to determine whether the cat was vaccinated for FIV.

One study indicated that some POC antibody test kits may better discriminate between FIV-infected and noninfected (vaccinated) cats, she said.2 As long as the cat was vaccinated more than 6 months before testing, the Witness FeLV-FIV (Zoetis) and Anigen Rapid FIV Ab/FeLV Ag test (BioNote) kits seemed to differentiate between antibodies from FIV vaccina­tion and those from natural infection better than the SNAP FIV/FeLV Combo (Idexx) could. “Veterinarians should be aware of these differences when using POC tests,” Dr. Little said.

Testing Kittens for FIV

Spread predominantly through fighting and biting, FIV is shed in high concentrations in the saliva, which contains infected white blood cells.3

However, kittens can have FIV antibodies without being infected, because they can acquire the anti­bodies from their mother if she was either vaccinated against FIV or naturally infected with the virus.

“There is a misconception that you can’t test kittens for FIV until they reach 6 months of age because of the effect of maternally derived antibodies [MDAs] against FIV,” Dr. Little said. By a few months after birth, however, kittens lose MDAs and are less likely to be seropositive for FIV antibodies. “In 1 study, 60% of 8-week-old kittens born to vaccinated queens were seropositive,” Dr. Little said, “but by 12 weeks of age, all kittens were seronegative.”4 The updated retrovirus management guidelines will address the mistaken idea that kittens younger than 6 months should not be tested.

When kittens older than 12 weeks test FIV positive, Dr. Little tends to believe that this signals infection and is not simply the result of vaccine-induced MDAs. These kittens should be retested with another methodology, such as a validated PCR assay, to determine infection status.

The bottom line: There is no magic age at which to start testing for either virus, according to Dr. Little—kittens should be tested for both FIV and feline leukemia virus (FeLV) promptly. “My goal is to test as many kittens as possible for both viruses, so I never delay testing them,” she said. “I test them as soon as I see them in the clinic.”

Most kittens do test FIV negative, Dr. Little said, which is a relatively reliable result. Because this virus does not easily transmit vertically, kittens typically do not acquire infection from the mother. For kittens that do test FIV positive and are not sick, she advised veterinarians simply to retest using a different POC test at the next vaccination visit 3 or 4 weeks later. “They usually test negative on the next visit,” she said. Alternatively, the kitten can be tested immediately using a valid PCR test.

Western Blot Testing for FIV

Because the consequences of a positive FIV-screening test are significant, follow-up testing should be performed.3 Although veterinarians can choose simply to use a different POC soluble antibody test, they could send blood samples to a laboratory for Western blot analysis to detect antibodies against various FIV antigens.3 However, Western blotting has been shown to be less sensitive and specific than POC screening tests.5

PCR Testing for FIV

Dr. Little reminded veterinarians that PCR testing by a referral laboratory should be used only in specific situations. These include a second-tier assessment for a kitten that tests FIV positive using a POC test, as well as in cats that received the FIV vaccine or in kittens with vaccine-induced MDAs. “This test is much less likely to pick up a positive result from an FIV vaccine,” she noted.

PCR is also useful in situations where a kitten has tested FIV positive and is not sick, but a follow-up test should not wait until the next vaccination visit. For example, if an owner has more kittens at home, veter­inarians can retest immediately using a validated PCR test. Dr. Little stressed the importance of using a PCR test that has been evaluated independently and has good sensitivity and specificity, such as the Idexx FIV RealPCR.2

“A positive result on a validated PCR test is very reliable,” Dr. Little said, noting the substantial genetic diversity among FIV subtypes. “And a negative result probably rules out infection, but we cannot be 100% sure about this, because sometimes no FIV virus is in circulation and thus it will not be detected by the PCR test.”

Testing For Feline Leukemia Virus

Currently available FeLV tests detect either antigens against the virus or the presence of viral nucleic acid, Dr. Little said. The POC ELISA test kits used in clinics detect soluble antigen (typically, p27 antigen) that circulates in the bloodstream. Referral labora­tories also perform ELISA tests for FeLV, as well as follow-up testing using either an immunofluores­cence assay (IFA) or PCR test—typically, to detect proviral DNA.

POC Kits for FeLV

Various POC tests are also available for use in clinics and shelters to detect FeLV. However, Dr. Little advised veterinarians to choose wisely because of variations in sensitivity and specificity. For example, in a recent independent study, the SNAP FIV/FeLV Combo test kit showed 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity for FeLV, but the VetScan Feline FeLV/FIV Rapid Test (Abaxis) had a sensitivity of just 85.6% and specificity of just 85.7%.1

How FeLV Vaccination Affects FeLV Testing

Unlike the situation in cats that have received FIV vaccination, FeLV vaccination does not interfere with testing for the virus, nor do FeLV-vaccine—induced MDAs, Dr. Little said.

IFA Testing for FeLV

The IFA tests for the p27 cellular-associated viral antigen in infected neutrophils and platelets. The pres­ence of viral antigen in these cells indicates that FeLV has infected the bone marrow, Dr. Little explained. This occurs later in infection, usually after 6 to 8 weeks, and represents a more progressive stage of FeLV infection. Consequently, she highlighted that 1 issue with IFA testing is that cats can be infected with FeLV but test negative using IFA if the infection has not yet reached the bone marrow. Another problem is that a low white blood cell count may prevent IFA from correctly detecting FeLV infection. “Remember that IFA is more important to use to determine whether FeLV infection has established in the bone marrow,” she emphasized.

PCR Testing for FeLV

PCR testing in a laboratory can also help veterinarians determine a cat’s FeLV status. For example, conducting PCR would be useful if a cat tested FeLV positive using a POC screening test but negative using IFA. “PCR turns positive earlier than any other test—as early as 2 weeks after infection,” Dr. Little said.

Veterinarians have a couple of options for retesting a cat that initially tests FeLV positive using a POC test kit. “You can retest the cat immediately using a different but reliable brand of POC test,” she said. However, many veterinarians go with the validated PCR testing option: “PCR has risen to top choice in such a scenario when you are trying to determine the cat’s true FeLV status after a positive screening test result.”

PCR should also be used to screen blood donors for FeLV infection. Although FeLV transmission occurs predominantly through saliva, the virus is also present in the blood and can be transmitted via blood transfusion.6,7 Veterinarians should screen all blood donor cats using both a routine antigen-screening test and PCR.6,7 “A routine antigen-screening test alone may fail to identify cats with regressive FeLV infection,” Dr. Little said. “They test negative for antigen on screening tests but typically are positive on PCR. And these cats can transmit infection to the blood transfusion recipient.”

Testing Kittens for FeLV

As with FIV, there is no firm rule about the youngest age for FeLV testing in kittens, Dr. Little said, but FeLV can transmit more easily than FIV from queen to kitten. Nevertheless, a kitten that has been infected with FeLV from its mother may still test negative until it seroconverts and tests positive.

Dr. Little advised veterinarians on the importance of considering the FeLV-negative kitten’s living environment, because other in-contact animals may also need to be tested. The virus can be spread both vertically and horizontally.3 Although cats typically acquire FeLV via the oronasal route by mutual grooming, they can also acquire it through bites.3 Viremic cats also shed FeLV in body fluids, including saliva, nasal secretions, feces, milk, and urine.3

Family testing can therefore be useful, Dr. Little said, especially for a young kitten that is still with its mother and/or litter mates. “If any of the cat’s family members test FeLV positive,” she said, “others will be suspect until we can sort out their individual FeLV status.”

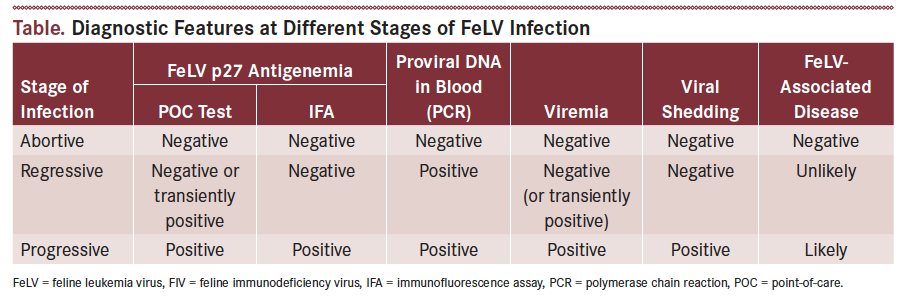

How the Stages of FeLV Infection Affect Testing

FeLV testing can be somewhat more complex than FIV testing because of the different stages of infection, Dr. Little said.8-10

Abortive Infection

After a cat is infected with FeLV, the virus initially replicates in the lymphoid tissue in the oropharynx. In some immunocompetent cats, the immune response eliminates the virus at this stage, before viremia occurs, and the infection is considered abortive. Cats with abortive FeLV infection thus test FeLV negative using all FeLV tests (Table). They show no evidence of viremia, and neither FeLV antigen nor proviral DNA can be detected in their blood.

Regressive Infection

If a cat fails to eliminate the virus, FeLV provirus can integrate into the DNA of the cat’s cells. After viral replication in the oropharyngeal lymphoid tissue, an initial wave of viremia occurs, and the virus infects lymphocytes and monocytes. These infected white blood cells circulate and transmit the virus throughout the body.

If the immune system can contain the FeLV infection at this point, it does not proceed and is considered regressive. Cats with regressive FeLV infection have a low risk of developing FeLV-related disease and do not transmit infection to other cats. However, viremia in these cats can be reactivated by concurrent disease or high-dose corticosteroid treatment, although this is considered uncommon.

Regressive infections may produce different patterns of positive and negative FeLV test results. Most commonly, these cats are FeLV negative using typical antigen-screening tests and just test positive using PCR (Table). “So, unless you have a reason to use the PCR test for FeLV, you might not know these regressively infected cats exist,” Dr. Little said. However, veterinarians should also be aware that the cat may have undergone PCR testing for FeLV during a period in which it was transiently antigen positive, she said. If retested at a later stage using an FeLVantigen- screening test, the cat will test negative.

Sometimes a regressively infected cat may transiently test FeLV positive using an antigen-screening test, Dr. Little said, which should also raise the suspicion of regressive FeLV infection. This scenario is more likely to occur in kittens older than 4 to 6 months because, as the immune system matures, they can eliminate or control FeLV infection more effectively.

Progressive Infection

If the cat’s immune system cannot contain the FeLV infection, the infection proceeds and extends to the bone marrow. A second wave of viremia occurs with viral shedding, and the infection is considered progressive. These cats become persistently viremic. “Progressively infected cats are the ones we are most concerned about because of their high risk of disease and ability to transmit infection to other cats,” Dr. Little emphasized.

Infection with FeLV early in life is the scenario that most likely will lead to progressive infection, Dr. Little said, because young kittens do not have robust immunity and are less likely to either eliminate the virus in the abortive stage of infection or become regressively infected by controlling it.

Progressively infected cats will test positive for FeLV using all tests (Table), she said, so they tend to be relatively easy to identify. Thus, if a cat tests FeLV positive using a POC antigen-screening test, veterinarians should at least consider that the cat might be progressively infected.

Conclusion

Regarding both retroviruses, Dr. Little emphasized that veterinarians may not be able to determine a cat’s infection status based on the results of any single test performed at a single time point. She also advised veterinarians not to pool blood samples from a group of cats for testing or select just 1 or 2 animals to sample from a litter or colony to reflect the overall FeLV or FIV status of the group.

Veterinarians must test all kittens for FIV and FeLV and use independently validated tests when possible, Dr. Little said. ”Whole blood is easier and faster to obtain than plasma,” she noted, adding that most test kits indicate that whole blood can be used for POC screening. Even if sick cats previously tested negative for either retrovirus, she advised veterinarians to retest, because the cat’s infection status may have changed.

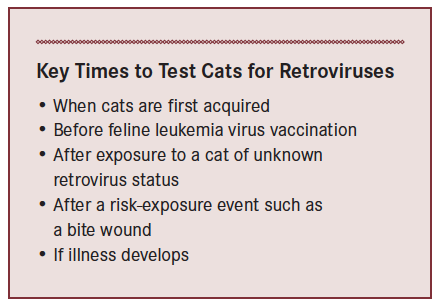

Highlighting the most important times to test cats for FeLV and FIV (Box), Dr. Little also stressed that “retrovirus testing should be part of the minimum database workup for any sick cat.”

Follow-up testing recommendations are changing for retroviruses, she said, with greater emphasis on validated PCR testing. The most recent version of the feline retrovirus management guidelines from the American Association of Feline Practitioners was published in 2008.3 However, updated guidelines will be published soon, she said, and will also address issues such as FIV testing in cats younger than age 6 months, core vaccinations in retrovirus-positive kittens, and retrovirus screening in shelter situations.

Dr. Parry, a board-certified veterinary pathologist, graduated from the University of Liverpool in 1997. After 13 years in academia, she founded Midwest Veterinary Pathology, LLC, where she now works as a private consultant. Dr. Parry writes regularly for veterinary organizations and publications.

References

1. Levy JK, Crawford PC, Tucker SJ. Performance of 4 point‐of‐care screening tests for feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31(2):521-526. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14648.

2. Westman ME, Malik R, Hall E, Sheehy PA, Norris JM. Determining the feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) status of FIV-vaccinated cats using point-of-care antibody kits. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;42:43-52. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2015.07.004

3. Levy J, Crawford C, Hartmann K, et al. 2008 American Association of Feline Practitioners’ feline retrovirus management guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2008;10(3):300-316. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.03.002

4. MacDonald K, Levy JK, Tucker SJ, Crawford PC. Effects of passive transfer of immunity on results of diagnostic tests for antibodies against feline immunodeficiency virus in kittens born to vaccinated queens. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004; 225(10):1554-1557.

5. Levy JK, Crawford PC, Slater MR. Effect of vaccination against feline immunodeficiency virus on results of serologic testing in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;225(10):1558-1561.

6. Nesina S, Katrin Helfer-Hungerbuehler A, Rion B, et al. Retroviral DNA—the silent winner: blood transfusion containing latent feline leukemia provirus causes infection and disease in naïve recipient cats. Retrovirology. 2015;12:105. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0231-z.

7. Wardop KJ, Birkenheuer A, Blais MC, et al. Update on canine and feline blood donor screening for blood-borne pathogens. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30(1):15-35. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13823.

8. Willett BJ, Hosie MJ. Feline leukaemia virus: half a century since its discovery. Vet J. 2013;195(1):16-23. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.07.004.

9. Hartmann K. Clinical aspects of feline retroviruses: a review. Viruses. 2012;4(11):2684-2710. doi: 10.3390/v4112684.

10. Hartmann K. Regressive and progressive feline leukemia virus infections — clinical relevance and implications for prevention and treatment. Thai J Vet Med Suppl. 2017;47:S109-S112.