Purdue: Avian Flu - Public Health Readiness and Response

A coordinated effort in 2016 helped to stave off a potential pandemic and reinforced the precautions required for veterinarians who may become involved with an avian flu outbreak.

Influenza is a good example of how animal and human health interconnect, according to Indiana State Public Health Veterinarian Jennifer Brown, DVM, MPH, DACVPM. Some outbreaks of avian influenza in poultry result in cooperative responses from multiple agencies at the local, state, and federal levels to implement plans to contain and stop the outbreak.

Presenting at the 2017 Purdue Veterinary Conference in West Lafayette, Indiana, Dr. Brown discussed key aspects of the public health response to the 2016 outbreak of H7N8 avian influenza virus in poultry in Dubois County, Indiana.

Human Influenza

“In a typical flu season, between 5% and 20% of the population gets the flu,” said Dr. Brown. More than 200,000 individuals are hospitalized due to complications of influenza infection, including sinus and ear infections, pneumonia, myocarditis, encephalitis, multiorgan failure, and sepsis, she added, and about 36,000 die from flu-related causes. Populations that are especially vulnerable include children younger than 5 years, adults older than 65 years, pregnant women, and patients with underlying health conditions.

RELATED:

- Avian Flu in Indiana

- Common Respiratory Emergencies in Birds

Of the 4 types of influenza virus (A, B, C, and D), Dr. Brown noted that types A and B cause most infections in humans and that type A is most often associated with severe disease. “Type A influenza viruses are the scariest of the 4 types,” she said, “because they are capable of major genetic change—which is what makes them so dangerous.” Type B influenza virus typically causes less severe disease, and type C causes mild or asymptomatic disease. Type D does not cause disease in humans, she noted.

Influenza viruses are changing constantly, and they accomplish this in 2 major ways: antigenic drift and antigenic shift. All influenza viruses are capable of antigenic drift, which causes small genetic changes that continually occur and are cumulative. Because the changes are small, the population may retain some background immunity to the changed virus, Dr. Brown said. In contrast, only type A viruses undergo antigenic shift, she said, because they have a segmented genome. Although antigenic shift occurs infrequently, it leads to major abrupt genetic changes, producing a novel virus to which the population has little immunity.

The 1918 influenza pandemic involved influenza type A, sub-type H1N1, said Dr. Brown. This was the deadliest influenza pandemic in modern history. It caused illness in 20% to 40% of the world’s population and killed about 50 million people. “Almost all human influenza cases since 1918 have been a result of descendants of this virus,” Dr. Brown emphasized.

Avian Influenza

Most of the influenza A viruses can also infect birds, said Dr. Brown, and wild aquatic birds are thought to be the natural reservoir of these viruses. Avian influenza refers to the disease caused by avian influenza type A viruses. These viruses cause high morbidity and mortality in birds and are very contagious. They are categorized as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) or low-pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) viruses based on their effects in chickens.

Although avian influenza type A viruses typically do not infect people, rare cases of human infection have been reported. In avian influenza outbreak events, humans can be at high risk for infection with the virus for various reasons, including having direct contact with birds (dead or alive), performing necropsies, sampling birds, moving birds, and checking feeders. Symptoms of infection in these cases are similar to those associated with human influenza virus infection and can include cough, fever, sore throat, and runny nose. Conjunctivitis alone can also occur. In severe infections, illness can progress to multiorgan failure or death.

HPAI Asian H5N1 and LPAI Asian H7N9 viruses have been responsible for most cases of avian influenza in humans worldwide, said Dr. Brown. Backyard poultry can spread the virus to humans via aerosol matter, direct contact, or fomites. HPAI H7N8 Outbreak in Indiana

Dr. Brown described some aspects of the animal and human health responses to the recent outbreak of H7N8 avian influenza virus in poultry in Indiana. On January 15, 2016, influenza A H7 virus was detected in a commercial turkey flock in Dubois County, Indiana, and was confirmed as HPAI H7N8.

Animal Health Response

Dr. Brown noted that state officials quarantined the premises and the owner began depopulating the flock to control spread of the disease. Surveillance of nearby commercial flocks also began. However, on January 16, H7 was detected in 9 more flocks in surrounding areas, she said. Eight of the viruses were confirmed as LPAI H7N8 and 1 was not ultimately isolated.

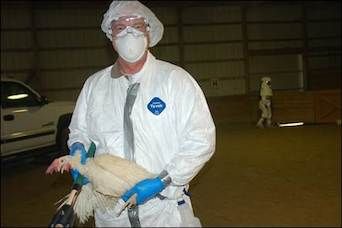

According to Dr. Brown, the response to control the outbreak was coordinated at federal, state, and local levels. Depopulation of infected sites was performed by farm employees, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), and low-level volunteer offenders within the Department of Correction (DOC). These teams depopulated 10 turkey flocks and 1 noninfected layer flock—a total of 414,223 birds, she said. In addition, flock employees and state and federal teams conducted surveillance of 65 commercial and 105 backyard flocks.

Composting crews and consultants performed in-barn composting, when possible, to dispose of the bird carcasses, and farm employees, the USDA, and company contractors cleaned and disinfected premises for virus elimination. The control area around the index flock was released after 38 days.

Human Health Response

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) consulted on the human health response, Dr. Brown noted that the Indiana State Department of Health coordinated the response, providing laboratory testing and antiviral medication, and consulted on infection control. The Dubois County Health Department was responsible for contacting potentially infected individuals and monitoring their illnesses.

According to the CDC, no cases of HPAI H7N8 infection were reported in humans. As a consequence, the virus was designated as a low-risk cause, but not a no-risk cause, of human disease.

Officials coordinating the response used this information to develop a plan to monitor responders to the outbreak. The main aspects of the plan included:

- Individuals exposed to HPAI had to be monitored for signs and symptoms of influenza-like illness for 10 days after their last possible exposure date.

- Individuals who developed influenza-like illness had to self-isolate until they could be tested.

- Individuals exposed to HPAI who were asymptomatic had no restrictions on their activity.

This plan aimed to facilitate prompt testing of ill responders by health care professionals to ensure that these individuals would receive appropriate treatment as soon as possible.

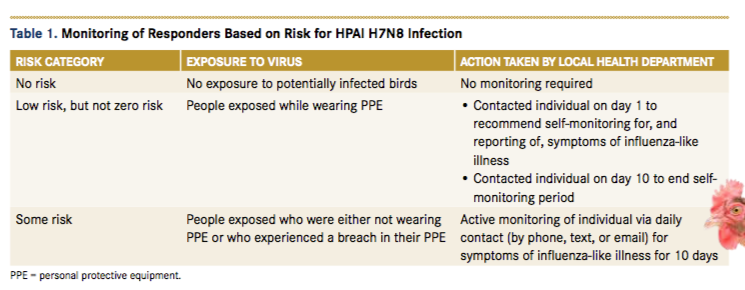

Working with guidelines from the CDC, Dr. Brown noted that officials coordinating the response developed 3 categories of disease risk to use when monitoring responders (Table 1). These categories were based on responders’ potential level of exposure to the virus. They defined influenza-like illness as symptoms of fever with cough and sore throat, conjunctivitis only, or any other symptoms.

According to Dr. Brown, this outbreak involved about 500 responders. Most were federal staff or federal contractors, she said, who were monitored by the USDA. However, the local health authority monitored local state residents and responders from the DOC (about 140 in total).

Dr. Brown indicated that 14 responders developed influenza-like illness during the monitoring period. This was not too surprising because the event occurred during flu season when this type of illness was expected. Twelve of these 14 responders were tested for the H7N8 virus, but all tested negative, she said. The remaining 2 responders were lost to follow-up.

Recommendations for Future Responders

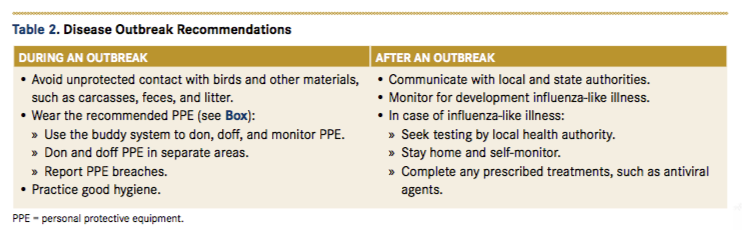

For veterinarians who might become involved in similar disease responses in the future, Dr. Brown shared several recommendations to help reduce the risk for becoming infected during and after an outbreak (Table 2).

She also advised responding veterinarians to stay up-to-date with their flu vaccination each year. “Although this won’t prevent you getting avian influenza, it will prevent you from having a human influenza virus during the response,” she said, emphasizing the potential risk for genetic reassortment in a person who is co-infected with an avian influenza type A virus and a human influenza type A virus.

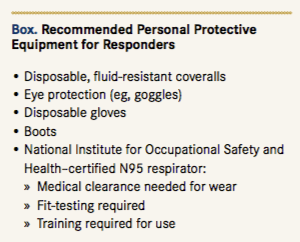

Dr. Brown recommended that veterinarians seek training on the proper use of personal protective equipment (Box) and be fit-tested to wear a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health—certified N95 respirator. Veterinarians should also follow avian infectious disease epidemiology updates from the USDA and their state board of animal health, she concluded.

Dr. Parry, a board-certified veterinary pathologist, graduated from the University of Liverpool in 1997. After 13 years in academia, she founded Midwest Veterinary Pathology, LLC, where she now works as a private consultant. Dr. Parry writes regularly for veterinary organizations and publications.